Lucy A. Hawkes

Marine Turtle Research Group

Centre for Ecology and Conservation, University of Exeter in Cornwall, Tremough Campus, Penryn, UK

Email: lhawkes{at}mail.seaturtle.org

URL: www.seaturtle.org

Presented to the BCG Symposium at the Open University, Milton Keynes, 27th March 2004

Introduction

The loggerhead sea turtle, Caretta caretta, occurs in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Found nesting in the temperate and subtropical regions of the Americas, the Mediterranean, Asia, Australia and Africa (Dodd 1988), the largest nesting aggregation of loggerhead sea turtles is thought to be at Masirah Island, Oman. The nesting population of the United States is the second largest in the world, with an average of 74,000 nests laid each year (Epperly et al. 1995). The species is listed as 'threatened' under the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973 and thus receives federal protection. Named for its enormous head, the loggerhead is the most commonly observed sea turtle species in North America, with adult size typically 70 - 90 cm straight-line carapace length (Dodd 1988). The loggerhead sea turtle feeds on benthic crabs and molluscs, with the blue crab, horseshoe crab and whelk thought to be main dietary items.

In the eastern United States, loggerheads have been found in waters as far north as Maine, south through to the Gulf Coast and Caribbean, but nesting is known only as far north as New Jersey (Dodd 1988) spreading south through Gulf Coast beaches to the Caribbean. Nesting in the eastern United States is reported to occur mainly between May and September (Carr et al. 1979, Shoop et al. 1985). Ninety per cent of the nesting effort is concentrated in Florida, while North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia host 2%, 6% and 2% respectively (Murphy and Hopkins 1984). Recent genetic surveys (Encalada 1998) have differentiated the United States population into three separate units, distinguishable by mitochondrial DNA. While the 'Southern subpopulation' (nesting on the Atlantic coast of Florida south of Cape Canaveral) is thought to be stable or increasing in size, recent reports (TIRN 2002) have documented the 'Northern subpopulation' (nesting on the coasts of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and north Florida to Daytona Beach) and 'Florida Panhandle subpopulation' (nesting on the Gulf Coast) as unstable or in decline.

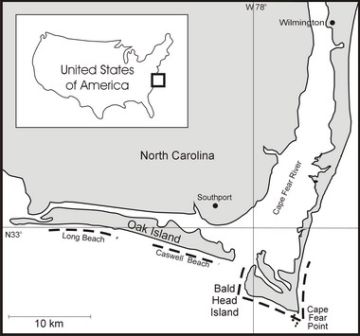

Whilst working as the Sea Turtle Programme Coordinator at the Bald Head Island Conservancy in North Carolina for two years, I was able to analyse a 24 year set of sea turtle nesting data collected at Bald Head Island, North Carolina (33°50' N, 77°57' W, Fig. 1). Detailed analyses of these data showed that despite 24 years of intensive nest protection and beach monitoring, there had been no appreciable increase in loggerhead nesting at Bald Head Island (Hawkes et al., in press).

All the beaches of North Carolina are surveyed and monitored for sea turtle nesting activity and all the nests found are protected with wire screens or checked daily for signs of predators. Again, despite the fact that so much effort has been directed at protection of nesting beaches for several decades, there has been no significant increase in the number of nests laid in North Carolina each year. Although protection of loggerheads on the nesting beaches is thorough, there are many threats to sea turtles in North Carolina waters including trawling operations, gill netting, dredging and recreational boating/fishing (NMFS and FWS 1991).

Factors external to the nesting environment (i.e. at sea) may be having a negative effect on the nesting population of North Carolina, increasing adult mortality or reducing recruitment to the adult population. In order to discover the habitats used by these turtles and to investigate and quantify the types and effects of potential threats at sea, the migratory pathways of post-nesting loggerhead sea turtles from North Carolina were investigated. The most efficient and practical way to do this is to track the post-nesting movements of these turtles by attaching transmitter packs to individual turtles and passively following the movements by remote signals received by satellites.

Methods

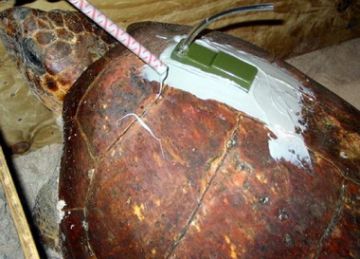

Four adult female loggerhead sea turtles were satellite tagged while nesting on the beaches of Bald Head Island, North Carolina, USA. The turtles were detained after egg laying and satellite transmitters were attached to their carapaces (Figs. 3 and 4) using standard methods (Godley et al. 2002). After thoroughly cleaning the carapace by removing all fouling organisms, the carapace was washed and the transmitter attached using slow-setting marine epoxy resin. Wooden blocks were then embedded into the resin in front of the transmitter (Fig. 5) to prevent damage when loggerhead turtles 'scratch' their carapaces underwater on rocky ledges and reefs. The turtles were detained on the beach until the resin was set and then released at the same spot as where they were first encountered.

The transmitters were deployed in July 2003 and tracking data were received via the ARGOS satellite receiver system. All data were downloaded and managed by SEATURTLE.ORG's STAT program (Coyne 2003) where live maps were generated and data made available to the public for educational purposes. Data describing sea surface temperatures and bathymetry were generated for each location using the data management tools in SEATURTLE.ORG's STAT program.

Results

Two of the four transmitters are currently active at time of press. The turtles made extensive movements along the eastern seaboard of the United States, travelling up to 640km north from the deployment point, through Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and New Jersey. Upon completion of their travels, the data from the tracking of these turtles will be subject to detailed analysis and further publication. British Chelonia Group members are invited to view the latest locations at: www.seaturtle.org/tracking/index.shtml?project_id=1 where live tracking maps are updated daily with the latest fixes. Additionally, all turtles involved in these tracking projects can be adopted as gifts to help raise awareness of marine turtles and to raise funds for additional tracking units. All proceeds support the sea turtle tracking programs of SEATURTLE.ORG and the organisation tracking the turtle that is adopted. Based on the success of the project in 2003, four more transmitters were deployed on nesting females at Bald Head Island in June (see latest locations at: www.seaturtle.org/tracking/index.shtml?project_id=25).

Acknowledgements

This project was sponsored by the Newport Aquarium, USA (http://www.newportaquarium.com), the PADI Project AWARE Foundation, the Whitener Foundation, Progress Energy, Juanita Roushdy and Anne Pickering. The greatest thanks go to the following for the collaborations that made this project possible: Brendan Godley and Annette Broderick of the Marine Turtle Research Group, Michael Coyne at SEATURTLE.ORG, Matthew Godfrey at the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission and the members, staff and interns of the Bald Head Island Conservancy. Particular thanks are due to Juanita Roushdy, Donna Finley, Anne Pickering and Peter Quinn for support and help throughout the project. Lucy Hawkes is supervised by Dr B. Godley and Dr A. Broderick at the University of Exeter in Cornwall. Many thanks to the British Chelonia Group for their support.

References

Carr, A.F.J., Jackson, D.R. and Iverson, J.B. (1979). Marine Turtles. In: A summary and analysis of environmental information on the continental shelf and Blake Plateau from Cape Hatteras to Cape Canaveral (ed. S. Gardiner), Maine. XIV: 1-45.

Coyne, M.S. (2003). Satellite Tracking and Analysis Tool (STAT), SEATURTLE.ORG, Inc. http://www.seaturtle.org/tracking/

Dodd, C.K. (1988). Synopsis of the biological data on the loggerhead sea turtle. Biological Report 88(14).

Encalada, S.E., Bjorndal, K.A., Bolten, A.B., Zurita, J.C., Schroeder, B., Possardt, E., Sears, C.J. and Bowen, B.W. (1998). Population structure of loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) nesting colonies in the Atlantic and Mediterranean as inferred from mitochondrial DNA control region sequences. Marine Biology 130: 567-575.

Epperly, S.P., Braun, J. and Veishlow, A. (1995). Sea Turtles in North Carolina waters. Conservation Biology 9: 384-394.

Godley, B.J., Richardson, S., Broderick, A.C., Coyne, M.S., Glen, F. and Hays, G.C. (2002). Long-term satellite telemetry of the movements and habitat utilization by green turtles in the Mediterranean. Ecography 25: 352-362.

Hawkes, L.A., Broderick, A.C., Godfrey, M.H. and Godley, B.J. (submitted). Status of nesting loggerhead turtles at Bald Head Island (North Carolina, USA) after 24 years of intensive conservation and monitoring. Oryx.

Murphy, T.M. and Hopkins, S.R. (1984). Aerial and Ground Surveys of marine turtle nesting beaches in the Southeast region, United States, p.73. U.S. final report to NMFS Contract No. NA83-GA-C-00021.

NMFS and FWS (1991). Recovery plan for the US population of loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta. Final Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service.

SEATURTLE.ORG http://www.seaturtle.org/tracking/index.shtml?project_id=1

Shoop, C.R., Ruckdeschel, C. and Thompson, N.B. (1985). Sea turtles in the southeastern United States: nesting activity as derived from aerial and ground surveys, 1982. Herpetologica 41: 252-259.

Turtle Island Restoration Network (2002). Petition to list the Northern and Florida panhandle subpopulations of the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) as endangered species throughout their range in the Western North Atlantic Ocean and designate critical habitat. Filed to: the Office of Endangered Species, National Marine Fisheries Service, U.S. Department of Commerce and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, United States department of the Interior, January 10, 2002.

Testudo Volume Six Number One 2004

Top