Karen A. Jensen and Indraneil Das

Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation,

University Malaysia Sarawak, 94300, Kota Samarahan,

Sarawak, Malaysia

Introduction

Borneo, the planet's third largest island, is located in the Malay Archipelago and is considered a centre of high global biodiversity. The island itself is under the jurisdiction of three countries – Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei Darussalam. Sarawak (Figure 1) is one of the two Malaysian states located on the island, the other being Sabah. It is the largest state in Malaysia, comprising 124,450 km2 of various forest types, urban and rural areas, and logged forest, all intersected by a lattice-work of rivers and tributaries. Sarawak's capital city is Kuching, which literally means 'cat' in the Malay language and is situated on the banks of the Sarawak River in the western part of the State.

Figure 1. Map of northern Borneo, showing location of Sarawak and adjacent regions. Inset: locator map of south-east Asia.

Native non-marine turtle species previously noted from Sarawak include two soft-shelled species (Family: Trionichidae): the Asian soft-shell turtle (Amyda cartilaginea) and the Malayan soft-shell turtle (Dogania subplana). Hard-shelled turtles known from Sarawak include seven species from the family Bataguridae: the painted terrapin (Callagur borneoensis), Malayan box turtle (Cuora amboinensis), Asian leaf turtle (Cyclemys dentata), spiny hill turtle (Heosemys spinosa), Malayan flat-shelled turtle (Notochelys platynota), Asian giant turtle (Orlitia borneensis), and the black pond turtle (Siebenrockiella crassicollis); and one species from the family Testudinidae, the Asian brown tortoise (Manouria emys). Two non-native turtle species are known to be established in some parts of Sarawak. These are the Chinese soft-shell turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis) and the red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta). All native species are protected in Sarawak. Commercial trade of reptiles in the State has been banned since 1998 (Sarawak Government Gazette, 1998). Upon entry into Malaysia in 1963, Sarawak was granted special rights and powers, not provided for the states within Peninsular Malaysia, to enact legislation autonomously (Sarawak Government Gazette, 1998, Sharma & Tisen 2000). The Wildlife Protection Ordinance was created in 1998. O. borneensis and C. borneoensis are listed as ‘Totally Protected’, and M. emys, A. cartilaginea, and D. subplana are listed as ‘Protected’. See Table 1 for a complete list of Sarawak and International protections regarding these turtle species.

| Scientific Name | Sarawak Wildlife Ordnance | IUCN | CITES |

|---|

| Amyda cartilaginea | Protected | Vulnerable | Appendix II |

| Dogania subplana | Protected | | |

| Callagur borneoensis | Totally Protected | Critically endangered | Appendix II |

| Cuora amboinensis | | Vulnerable | Appendix II |

| Cyclemys dentata | | Lower Risk | Appendix II |

| Heosemys spinosa | | Endangered | Appendix II |

| Notochelys platynota | | Vulnerable | Appendix II |

| Orlitia borneensis | Totally Protected | Endangered | Appendix II |

| Siebenrockiella crassicolis | | | Appendix II |

| Manouria emys | Protected | Endangered | |

Table 1: Non-marine turtles of Sarawak and their status in the Sarawak Wildlife Ordnance, IUCN and CITES Appendices.

Most of the native freshwater turtles and tortoises found in Sarawak are listed by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) (www.iucnredlist.org). The IUCN is the world's largest conservation network, consisting of scientific experts and policy makers from more than 62 countries and 800 non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The IUCN keep a record of those species most in need of conservation attention through their 'Red List'. Listed as critically endangered is C. borneoensis. Listed as endangered are H. spinosa, M. emys and O. borneensis. Classified as vulnerable are A. cartilaginea, C. amboinenesis and N. platynota. Classified as Lower Risk is C. dentata. Lastly, D. subplana and S. crassicolis have not been listed by the IUCN.

Malaysia is a party to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an international agreement between 169 countries. Its aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. The species covered by CITES are listed in three Appendices, according to the degree of protection they need. All native species of non-marine turtles found in Sarawak are listed under Appendix II in Malaysia of the CITES Treaty, with the exception of M. emys and D. subplana (www.cites.org).

These turtles play important roles in the dynamics of freshwater ecosystems (Ernst and Barbour, 1989; Moll and Moll, 2004; Pritchard, 1979), but, apart from a few species from temperate regions of North America, their ecology has attracted little attention from scientists. This paper represents a summary of a study on the natural history and use of A. cartilaginea in Sarawak, with notes on other freshwater turtle species.

Materials and methods

The primary study area was Loagan Bunut National Park. The Park is in the central part of the State and within a three hour drive from the town of Miri. Coordinates for the Park Headquarters are 3°44' - 03° North and 114°09' - 114°17' East. Field work was concentrated at the Park but two visits were made to Balai Ringin, a fishing village, about two hours driving distance from Kuching. Coordinates for Balai Ringin are 01° 03' 00'' North and 110° 45' 00'' East. Both sites are located within peat swamp forests (Figure 2). Information gathered pertaining to cultural use of turtles was collected opportunistically throughout Sarawak.

Loagan Bunut National Park contains the only freshwater floodplain lake in Sarawak (Figure 3) (Sayer, 1991), encompassing 650 ha when at its maximum level. The lake is completely dry during prolonged drought. Annually, the lake dries up between three and six times, usually in February, May and June.

A variety of techniques were attempted to see which was the most effective for capturing A. cartilaginea. Hoop traps, commonly used to catch freshwater turtles in the Western hemisphere (Frazer et al., 1990; Legler, 1960; Vogt, 1980) were employed. Native hoop traps called 'bubu' were also used and another local fishing device called a 'selambau' used. The selambau is a special system of scoops and nets attached to long poles and stretches across a river. The most effective albeit labour intensive method of capturing soft-shell turtles was to feel in the mud for the turtles, better known as muddling. Hiking in the forests allowed opportunistic capture of other turtle species.

Upon capture, turtles were immediately transported to base camp where each animal was weighed, measured, photographed and their stomachs flushed using methods developed by Legler (1977) and following the modifications of Fields et al. (2000). Measurements were made to the nearest millimetre (mm), and weight recorded to the nearest 0.1 kilogram (kg). Standard measurements such as curved and straight carapace length, carapace or shell height and width were all recorded. Turtles were kept in plastic basins typically for a 24 hour period or until they provided a faecal sample. Soft-shell turtles were tagged following the method documented by Dreslik (1997). Hard-shelled turtles were tagged by attaching a field number with clear epoxy to a rear marginal scute.

Sex was visually determined, if possible, and recorded for each turtle captured. Sexual dimorphism differs for the various Bornean freshwater turtle species. For A. cartilaginea, males have a relatively longer tail that extends to the edge of or beyond the edge of the carapace. This difference in tail length between the sexes is apparently similar for D. subplana. In all but one of the Bataguridae species, C. amboinensis, H. spinosa, N. platynota, and S. crassicollis, males have a concave plastron, and in N. platynota and S. crassicollis males also have longer, thicker tails. The other Bataguridae species found during this study, C. dentata, does not exhibit any known sexual dimorphism aside from females outgrowing male turtles. Juveniles of all species were not separated by sex because these species are not known to be sexually dimorphic prior to sexual maturity.

Radiographs were taken to determine reproductive condition of females following Gibbons and Greene (1979) and recommendations by Hinton et al. (1997). This results in the same exposure to x-rays as an adult human shoulder. The technique is 100% accurate for determining clutch sizes (Gibbons & Greene, 1979) and does not place adults, embryos, or populations into health risks if the procedures are properly followed (Hinton et al., 1997). The major advantage of this technique over dissection is that individuals need not be killed.

Results

A total of 34 individual turtles from four species were found from the study sites and two other localities. Although turtles were marked and released, no animals were caught a second time.

| | LBNP | Balai Ringin | Matang Wildlife Centre | Mulu | Total |

|---|

| Amyda cartilaginea | 14 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Adult males | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Adult females | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Juveniles | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Cuora amboinensis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Adult males | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adult females | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Juveniles | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Cyclemys dentata | 6(1)* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Adult males | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adult females | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Juveniles | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Heosemys spinosa | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Adult males | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Adult females | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Juveniles | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Table 2: Total number of individuals for each turtle species caught during this project. Asterisk refers to the numbers in parenthesis as unsexed individuals

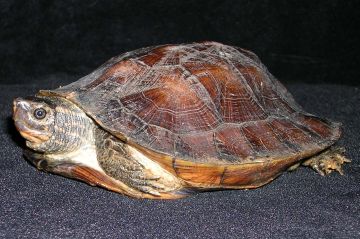

At Loagan Bunut National Park, 14 A. cartilaginea were captured during this study (Figure 4). Six males, six females and two juvenile turtles were examined. Six C. dentata were collected (Figure 5); one female, four juveniles, and one carcass. Three juvenile C. amboinensis were collected (Figure 6). One adult female C. amboinensis and one adult N. platynota were provided by Park personnel from their longhouse for examination. One juvenile H. spinosa recorded was based on a photograph by a Park employee and identified by the authors.

At Balai Ringin, a total of three freshwater turtle species were seen. Only five A. cartilaginea were caught and examined at Balai Ringin. There were four females, and one juvenile. Additionally, one female C. dentata and one female H. spinosa were examined.

An additional five turtle species were found incidentally in other localities. One D. subplana was found on the banks of the Bayur River at the base of the Penrissen Mountain Range, near Kuching. Two P. sinensis, an introduced soft-shell turtle species, were incidentally seen in Kuching. One A. cartilaginea was examined while at Gunung Mulu National Park, a World Heritage Site in Sarawak and located about a four hour boat ride, upriver from Loagan Bunut National Park. Three H. spinosa were incidentally found and examined (one female, one male, one juvenile) (Figure 7) at Kubah National Park and the adjacent Matang Wildlife Centre, which is located outside of Kuching.

Results of radiography indicated that two turtles were found to be gravid with eggs. One C. dentata, from Balai Ringin, had a clutch of two eggs; one H. spinosa had a single elongated egg. Both of these turtles were immediately released at their capture sites. The D. subplana was found to be gravid with 11 eggs in various stages of development, indicating that it may have been carrying two clutches.

The dominant foods found in both stomach and faecal analysis of A. cartilaginea are plant materials, followed by unknown vertebrate remains, indicating that this species is an omnivore. Tendencies towards omnivory have been reported for another trionychid turtle, the African soft-shell turtle (Trionix triunguis) (see Branch, 1988; Ernst & Barbour, 1989), and the tendency to feed upon vertebrate carcasses is known from other soft-shell species (Akani et al., 2001, T. triunguis; Das, 1995, the Ganges soft-shell turtle [Aspideretes gangeticus] and the Indian peacock soft-shell turtle [Aspideretes hurum]; Taskavak & Atatür, 1998, Euphrates soft-shell turtle [Rafetus euphraticus]).

The stomach of D. subplana contained the remains of a large freshwater crab and a freshwater snail. The other turtles examined for diet, C. amboinensis, C. dentata, and H. spinosa, all had predominately vegetative material including seeds and fruits. One faecal sample from a H. spinosa, an adult female, contained several phalanx bones of a small primate, either a langur (Presbytis spp.) or macaque (Macaca spp.).

Turtles seem to be used primarily for food, and, on a smaller scale, for pets or socio-religious purposes. The most desirable species for food seems to be A. cartilaginea. Turtles at the outdoor markets may be for sale, but not obviously. Only at a few markets where the fishmongers knew and trusted the authors would they show turtles for sale. Since the implementation of the Sarawak Wildlife Ordnance (Sarawak Government Gazette, 1998), the authors have observed a decrease in the obvious sale of protected species. Occasionally one could find other turtle species for sale in ‘pet’ sections of the outdoor markets, alongside puppies, rabbits, and tropical fishes. These were often T. scripta, native to North America and popular in the local pet trade, and also C. amboinensis. Buddhist temples in Sarawak often have ponds holding turtles, and in the Reservoir Park in Kuching one can occasionally see people releasing turtles, which is a Buddhist tradition.

Interviews with turtle hunters and fishermen at longhouses indicate that A. cartilaginea is a prized food item. In the more remote areas of Sarawak, hunting practices are generally traditional and have a long history. The most frequently used methods of catching turtles are either by baited hooks or by muddling for them during the dry season. We were told that muddling during the dry season may yield more turtles, although the effort is labour-intensive.

A. cartilaginea are attractive from a market perspective because they are large and hardy, staying alive for days without food. Many people will place an opportunistically caught turtle in a basin or tank of water until there is a time to eat or sell. This is important in rural communities without refrigeration, or for fishermen on multi-day fishing trips and for shipping turtles to towns from upriver. Also, these turtles are a luxury item for those who have relocated to urban areas and may live more than a day's journey away from their rural homes but maintain cultural and dietary preferences from home. They continue to eat wild meat even when they have easily available alternatives (Bennett & Robinson, 2000).

Discussion

Collection of large sets of field data on A. cartilaginea is difficult in Sarawak where this species is actively hunted for food by nearly all indigenous peoples and the species is consequently not easily captured. Additionally, it appears to be an extremely elusive animal. It may not move great distances and it cannot be seen from above or in the water, which is highly turbid with low or no visibility, the colour being either milk chocolate brown or black as ink. Additionally these turtles apparently do not bask.

There are no records of the volume of the turtle trade in Sarawak and no historical records of population abundance of any non-marine turtle species. However, given the life history and ecology of most turtle species, it is doubtful whether present levels of exploitation are sustainable. Congdon et al. (1993) demonstrated that long-lived organisms such as turtles have life history traits that severely constrain the ability of turtle populations to respond to disturbances such as overexploitation. These traits include delayed sexual maturity and often high and variable nest mortality.

Extirpation of these animals from the ecosystem also has negative effects on the biodiversity. These animals serve roles as seed dispersers, scavengers, predators, and potentially prey in the forest and wetlands. Removal of a faunal or floral component from an ecosystem can disrupt its functioning (Gunderson & Holling, 2002; Odum, 1993). Hunting wildlife to extirpation negatively effects human populations that depend on it and the resource must be replaced if people are to maintain familiar lifestyles.

Recommendations

Continued research is necessary for all species of freshwater turtles and tortoises found in Sarawak. Future studies of freshwater turtles should include population estimates for each species in Sarawak. This would require an extensive amount of time, as the best way to accomplish this would be with capture-mark recapture in a subset of different habitat types and then extrapolation of this data to habitats across Sarawak. Information on reproductive biology from wild populations, for all species, is still needed. Information on habitat use, home range and other life history requirements is needed and necessary for proper wildlife and reserve management.

Once a base-line inventory is established a long-term monitoring program should be implemented. Development of monitoring programs not only for freshwater turtles but for other keystone natural and physical resources should be a standard operation for resource managers. Long-term monitoring provides early warning signals that indicate changes that could impair the long-term health of natural systems. Early detection of potential problems allows resource managers to take steps to restore ecological health of natural and physical resources before serious damage can happen.

Freshwater turtles and tortoises are clearly an important part of the local culture in Sarawak. Comprehensive surveys of the turtle trade in Sarawak are needed to determine the level of exploitation and if there is also export to the international wildlife market.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible with the support and funding from the British Chelonia Group (BCG), Chelonian Research Foundation's (CRF) Linnaeus Fund, University Malaysia Sarawak, and the UNDP-GEF Malaysia Peat Swamp Project. Special thanks to BCG's Bob Langton, and CRF's Anders G. J. Rhodin for their support and encouragement of this project.

References

Akani, G.C., Capizzi, D. & Luisselli, L. (2001). Diet of the softshell turtle, Trionyx triunguis, in an Afrotropical forested region. Chelonian Conserv. & Biol. 4(1):200–201.

Bennett, E.I. & Robinson, J.G. (2000). Hunting of wildlife in tropical forests: implications for biodiversity and forest peoples. The World Bank, Washington D.C., 56 pp.

Branch, B. (1988). Field guide to the snakes and other reptiles of southern Africa. New Holland Publishers Ltd., London, 144 pp.

CITES (2004). Species Database. www.cites.org/eng/resources/species.html

Congdon, J.D., Dunham, A.E. & van Loben Sels, R.C. (1993). Delayed sexual maturity and demographics of Blanding's turtles (Emydoidea blandingii): implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. Cons. Biol. 7:826–833.

Das, I. (1995). Turtles and Tortoises of India. Oxford University Press, Bombay, 176 pp.

Dreslik, M.J. (1997). An inexpensive method for creating spaghetti tags for marking trionychid turtles. Herpetol. Rev. 28(1):33.

Ernst, C.H. & Barbour, R.W. (1989). Turtles of the World. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. and London, 313 pp.

Fields, J.R., Simpson, T.R., Manning, R.W. & Rose, R.L. (2000). Modifications of the stomach flushing technique for turtles. Herpetol. Rev. 31:32–33.

Frazer, N.B., Gibbons, J.W. & Owens, J.T. (1990). Turtle trapping: preliminary tests of conventional wisdom. Copeia 1990(4):1150–1152.

Gibbons, J.W. & Greene, J.L. (1979). X-ray photography: a technique to determine reproductive patterns of freshwater turtles. Herpetologica 35(1):86–89.

Gunderson, L.H. & Holling, C.S. (Eds.) (2002). Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Island Press, Washington, 450 pp.

Hinton, T.G., Fledderman, P.D., Lovich, J.E., Congdon J.D., & Gibbons, J.W. (1997). Radiographic determination of fecundity: is the technique safe for developing turtle embryos? Chelonian Cons. & Biol. 2(3):409–414.

IUCN. (2004). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. www.iucnredlist.org

Legler, J.M. (1960). A simple and inexpensive device for trapping aquatic turtles. Utah Academy Proc. 37:63–66.

Legler, J.M. (1977). Stomach flushing: a technique for chelonian dietary studies. Herpetologica 33:281–284.

Moll, D. & Moll, E.O. (2004). The Ecology, Exploitation and Conservation of River Turtles. Oxford University Press, New York, 393 pp.

Odum, E.P. (1993). Ecology and our endangered life-support systems. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Massachusetts, 283 pp.

Pritchard, P.C.H. (1979). Encyclopedia of Turtles. T.F.H. Publications, Neptune, N.J., 895 pp.

Sarawak Government Gazette. (1998). Laws of Sarawak. Chapter 26. Wildlife Protection Ordinance, 1998. 46 pp.

Sayer, J. (1991). Rainforest buffer zones. Guidelines for Protected Area Managers. IUCN Forest Conservation Programme, Cambridge, UK, 94 pp.

Sharma, D.S.K., & Tisen, O.B. (2000). Freshwater Turtle and Tortoise Utilization and Conservation Status in Malaysia, pp 120–128. In: Proceedings of a Workshop on Conservation and Trade of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises in Asia (van Dijk, Stuart & Rhodin, eds.). Chelonian Research Monographs. #2.

Tashavak, E & Atatür, M.K. (1998). Distribution and habitats of the Euphrates softshell turtle, Rafetus euphraticus, in southeastern Anatolia, Turkey, with observations on biology and factors endangering its survival. Chelonian Conserv. & Biol. 3(1):20–30.

Vogt, R.C. (1980). New methods for trapping aquatic turtles. Copeia 1980(2):368–371.

Testudo Volume Six Number Three 2006

Top